Willow Flycatcher

General Description

The Willow Flycatcher is one of the largest flycatchers in the genus Empidonax, with a relatively flat forehead and distinct peak on the rear of its crown. It is gray in color, with buffy or light-gray wing-bars and an almost invisible white eye-ring. The lack of visible eye-ring helps distinguish it from the other Empidonax flycatchers. It has a pale breast and white throat, and the base of the lower mandible is yellow. Its bill is broad with a pale lower mandible and a long, broad, straight-sided tail.

Habitat

This aptly named bird is found in willow thickets and other brushy areas near streams, marshes, or other wetlands, and in clear-cuts and other open areas with nearby trees or brush.

Behavior

Willow Flycatchers typically forage in the shrub layer, or in low trees. They watch from a perch, fly out to grasp prey in quick darts, and return to the perch. They also glean prey from twigs and branches as they hover in the foliage.

Diet

Insects, especially flying insects, are the most common prey.

Nesting

The male sings to defend his territory, although the female has been known to sing as well. The female builds a low nest in a willow, bracken fern, or rose. The nest is usually an open cup of grass and bark, lined with soft plant down and other material. Sometimes strips of plant material hang from the bottom of the nest. The female incubates three eggs for 13 to 14 days, and both parents help feed the young. The young take their first flights at 13 to 15 days, but often remain near the nest for three or four more days, and continue to follow their parents around the territory until they are 24 to 25 days old. The short breeding season allows for only one clutch a year.

Migration Status

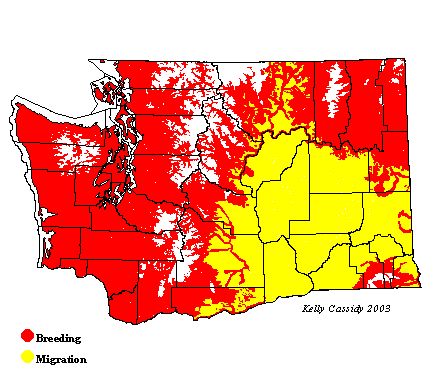

Willow Flycatchers winter in the Amazon Basin and are one of the latest birds to arrive in Washington in the spring. It is often the end of May before they are back on their breeding grounds. They head south in early fall, leaving Washington in late August or early September.

Conservation Status

This species has declined in some areas due to loss of streamside habitat, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service lists the southwestern population as a subspecies-of-concern. Willow Flycatchers in Washington experienced significant declines from 1966 to 1979, according to the Breeding Bird Survey. During the period between 1980 and 2000, the species still suffered a decline, but to a lesser degree, indicating that there may be a reversal of the trend, or at least stabilization, in the years to come. Despite their decline, Willow Flycatchers are still very common in western Washington. They are less common and more locally distributed east of the Cascades. River-corridor channelization, overgrazing, dam construction, and urbanization all degrade Willow Flycatcher habitat. With the listing of many Northwest salmon populations under the Endangered Species Act, many rivers are undergoing restoration to improve the habitat for salmon, which should also improve habitat for Willow Flycatchers and other riparian species.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Willow Flycatchers are common in appropriate habitats such as clear-cuts, to elevations of at least 3,000 feet on both sides of the Cascades. They are rare along the outer coast and uncommon on the western side of the Olympic Peninsula. Migrants and non-breeders are sometimes seen in the Columbia Basin.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | U | U | |||||||

| Puget Trough | U | C | C | C | U | |||||||

| North Cascades | U | C | C | F | R | |||||||

| West Cascades | R | C | C | C | F | |||||||

| East Cascades | R | U | U | U | U | |||||||

| Okanogan | R | C | C | C | R | |||||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | ||||||||

| Blue Mountains | U | F | F | F | U | |||||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | F | F | F | F |

Washington Range Map

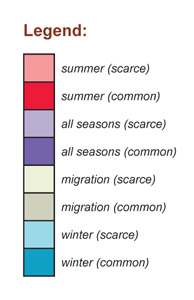

North American Range Map

Family Members

Olive-sided FlycatcherContopus cooperi

Olive-sided FlycatcherContopus cooperi Western Wood-PeweeContopus sordidulus

Western Wood-PeweeContopus sordidulus Alder FlycatcherEmpidonax alnorum

Alder FlycatcherEmpidonax alnorum Willow FlycatcherEmpidonax traillii

Willow FlycatcherEmpidonax traillii Least FlycatcherEmpidonax minimus

Least FlycatcherEmpidonax minimus Hammond's FlycatcherEmpidonax hammondii

Hammond's FlycatcherEmpidonax hammondii Gray FlycatcherEmpidonax wrightii

Gray FlycatcherEmpidonax wrightii Dusky FlycatcherEmpidonax oberholseri

Dusky FlycatcherEmpidonax oberholseri Western FlycatcherEmpidonax difficilis

Western FlycatcherEmpidonax difficilis Black PhoebeSayornis nigricans

Black PhoebeSayornis nigricans Eastern PhoebeSayornis phoebe

Eastern PhoebeSayornis phoebe Say's PhoebeSayornis saya

Say's PhoebeSayornis saya Vermilion FlycatcherPyrocephalus rubinus

Vermilion FlycatcherPyrocephalus rubinus Ash-throated FlycatcherMyiarchus cinerascens

Ash-throated FlycatcherMyiarchus cinerascens Tropical KingbirdTyrannus melancholicus

Tropical KingbirdTyrannus melancholicus Western KingbirdTyrannus verticalis

Western KingbirdTyrannus verticalis Eastern KingbirdTyrannus tyrannus

Eastern KingbirdTyrannus tyrannus Scissor-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus forficatus

Scissor-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus forficatus Fork-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus savana

Fork-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus savana